Like any icon, this little narrative is not to be read literally. It is to be read by our souls. The details are intended to shake the mind loose from its obsession with the rational.

At times in the Gospels, we find ourselves face-to-face with the living God. We are filled with awe as suddenly we are surrounded by the sublime, and we understand very well why the demons quake. Yet, other Gospel lessons invite us into joyful scenes. We are filled with wonder and the light of innocence. We are elevated above this gritty world to breathe pure and Divine air. It is this second kind of Gospel narrative we enter today.

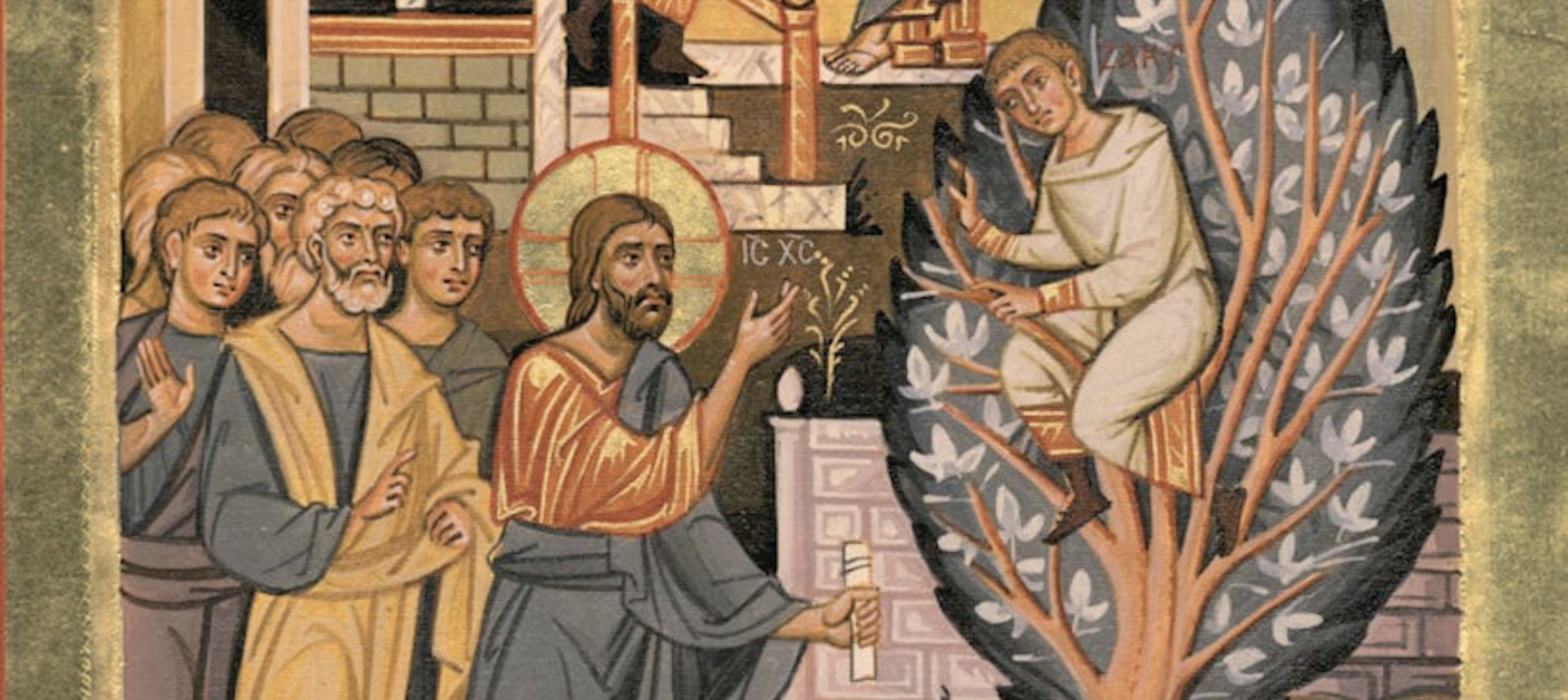

Which Sunday school classroom does not feature a depiction of Zacchaeus? He is always a cartoonish figure, up in a tree, usually appearing to be a boy. Perhaps the picture is drawn in crayon by a student. Without explaining it or really understanding it, these young artists are connecting to something powerful in St. Luke's Gospel.

Also beyond their knowledge is the meaning of the word Zacchaeus. It is not Koine Greek, nor does it appear in lexicons of Classical Greek. It is also not Aramaic, the language also spoken in first-century Judah. (They did not speak Hebrew.) It is from the Hebrew language and means pure or innocent. It was used not as a name but used to denote a young boy — something like lad or nipper or little shaver to people of the last century. It summons the spirit of boyish youth: tree-climbing, running with abandon even in a crowd, and innocent freedom. That is, Luke is presenting us with an icon, not a snapshot of a historical scene nor a portrait striving for material exactness. No. Rather, he paints an idea, or should I say a spiritual ideal: that of the spirit without guile. And we think of Chapter One in St. John's Gospel when Jesus says of Nathanael:

| "Here is an Israelite in whom there is no guile." (Jn 1:47) |

The occasion, of course, is Jesus calling His Disciples. The Lord is looking for open and honest spirits among His followers, not deception, which is a defining character trait of the evil one, the father of lies (Jn 8:44). And, of course, during the period of the Incarnation, deception is a master theme, whose great icon is the Persian Temple built on Mt. Zion and the spread of the hybrid Persian religion, Judah-ism. It is not for nothing that Jesus' betrayer is named Judas, a variant spelling of Judah.

Like any icon,

this little narrative

is not to be read literally.

It is to be read by our souls.

The details are intended to shake the mind

loose from its obsession with the rational.

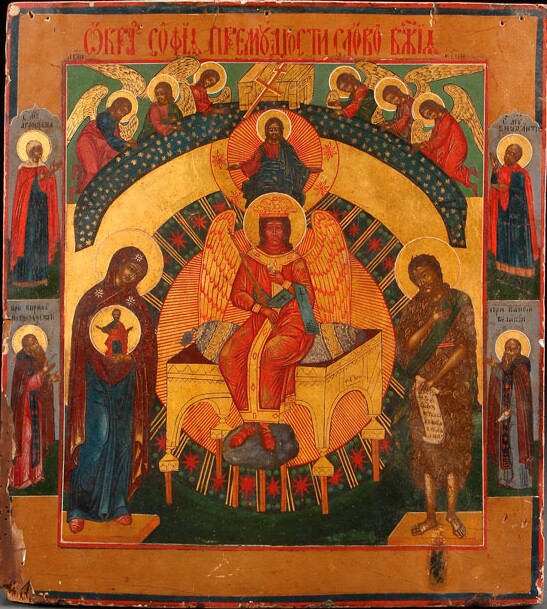

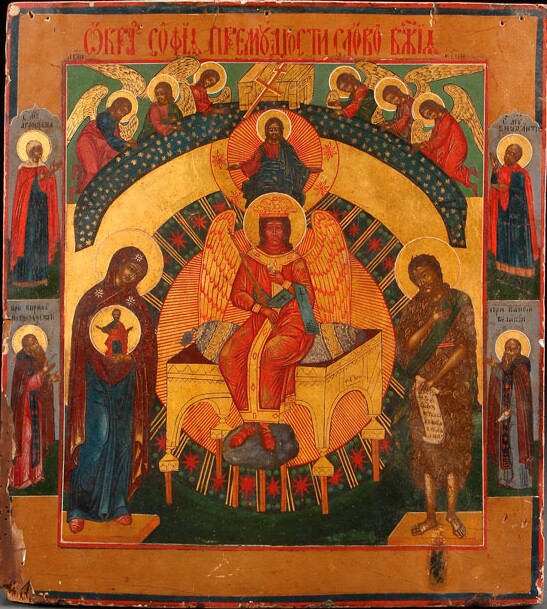

Consider the holy icon "Sophia, Wisdom of God." We see a red faced angel adorned with a crown with enormous wings and sitting upon a throne. The rational mind asks, "Are we to conclude the Holy Trinity has become a fellowship of four?" Or "Is this angelic figure the Holy Spirit?" But the icon's title tells us that this is a rendering of Holy Wisdom, which is the Logos, the Son of God. Jesus is depicted elsewhere in the icon .... more than one. The mind rebels at this paradox. "What is the meaning of this?!" the rational mind objects. Yet, as Origen reminds us, paradox is precisely the "leaping off" point, where we depart from rational analysis behind and give ourselves over to spiritual contemplation. Origen said, If there anything at the literal or historical level that gives offense to logic, that this can't possibly be, then that is your cue that you have entered into mystery, into the spiritual domain of Scripture.

The domain nominated by St. Luke in our Gospel lesson is discipleship. When Jesus calls us, He does not want us to be willful. He does not want us to "live in our heads" which are full of previous assumptions and hardened opinions. You can imagine a willful novice entering a monastic community who constantly says, "This is way to do it .... that's wrong .... I know!" No. This will never do. In fact, He always asks us to burn down our whole world, for it is only then that we are able to begin our new lives in Him.

Jesus roams the Levant imploring us to be transformed back to our former innocence (Mt 18:3). His Forerunner had preceded him exhorting us to return to purity, washing away the polluting effects of experience. Our scene today presents this in perfection: a grown man who has reverted to His boylike innocence.

Certainly, his name is not literally Zacchaeus. His element has been the grave upper reaches of Roman Society. The chief tax collector would have been a member of the Societas publicanorum of the Equestrian class, just below the Senatorial class. Under the Roman Republic, he would have supervised large projects such as the ambitious harbor at Caesarea Maritima or the great Temple to Augustus Caesar at Banaeus. He would have been responsible for supplying Roman Legions in the field with food and other necessary materiel. With the rise of a large bureaucracy during the early Empire, the importance of the Chief Publican began to diminish, but whatever the scope of his responsibilities, he would have been entrusted with our equivalent of millions of dollars. And Caesar's high officials would not have risked hiring a foolish man often appearing as an exuberant boy, racing about in the crowd. He must inhabit a certain gravitas. He must choose the one on whom he smiles (and that person counts it a prize). He must maintain a certain aloofness.

But if this man should break from the decorum of imperial society, upon which all eyes are glued, what it can be mean? Surely, it must be something very great. For this man has played the game of the Roman official and played it at a very high level. But through it all, he never lost sight of his soul, and his soul somehow has retained its childlike glow. That is the great principle, now unveiled, that holds all captive. Now in the presence of God, he throws off the distinguished robes of office, and appears in a garment he knows God will not despise — the ebullient, innocent heart of a boy.

The scene is not to the extreme of, say, the Apostles skinny-dipping at the waterhole: Petey, Johnny, Tommy, and Jimmy. Nonetheless, the name Zacchaeus is precisely that: "waterhole language." And it is of a piece with the outlandish scene of a grown man racing about in the crowd and climbing trees.

Now, let me be clear. Do I believe that a rather short, chief tax collector turned his back on his public office (as Levi/Matthew had) and became a follower of Jesus? Certainly, I do. But you see, St. Luke has offered us a stylized icon inviting us into a mystery, and that mystery is intimately tied to Metanoeite!, which the Baptist had cried in the wilderness and the Lord Jesus had preached. This called Zacchaeus has made a U-turn, and he has arrived to acceptable place: back to his innocence.

Did you notice that Jesus makes no demand of him: "In order to follow Me, you must first sell all that you have and give to the poor." No. Zaccaeus, when has Jesus alone, offers these things eagerly. Jesus merely receives them as precious treasure, for this is spiritual treasure.

We say that the passage from innocence to experience is necessary rite. But what exactly do we mean? What is this adult world we are passing into? We recently reflected on the word, adolescence (adolescere) and its etymological connection to adult (adultare). It means "to pollute, to defile, to commit adultery." Certainly, the signature sin of adulthood is illicit or impure sexuality, which is unknown to the child .... but very well known to most adults.

What would an icon of Metanoia look like? After all, here is the very heart of Christianity: the transformation from experience back to purity. Jesus says, "Today salvation has come to this house" (Lu 19:9). Salvation, σωτερία / sotería — this word might mean a number of things including safety or protection. But the definition that makes most sense to me is safe return in the sense of a rescue, and a return to Eden. Did not the man of Eden purify people for this purpose: safe return.

You know, God cannot save us. He has no magic wand to turn us from this to that. And if He had, that would make Him no more than a puppet master or a commander of robots. Moreover, if this were true, He would not have sent His forerunner crying in the wilderness "Metanoeite," and He would not have made this word the hallmark of His ministry. Sotería must come from within. We must effect this rescue and then meet with God's grace. We must break loose. We must take the garbage out. He will not do it for us. If there is stench in the Hermitage, we must find this dead rat that is festering. There is no other remedy.

From what must we be rescued? St. John the Evangelist tells us, it is the world with its inevitable entanglements of carnality and materialism, — the two driving wheels operating within the human breast by and large.

If we had visitors from foreign galaxies, who turned out to be anthropologists, and they visited the various countries on earth, what would they say about the United States. Well, the two most important things to the people of that nation are materialism and carnality. Their children are trained in the first, and their culture is soaked through with the second.

Most of us learn, sooner or later, that this is our poison, that we are addicted to this destructive nectar. We call it dopamine these days. But this is a way of saying, pointing merely to the proximate "bio-engines," that we are demon-possessed by our own doing. We have invited these demons in. We call this experience.

But the rescue must proceed first from the heart, and then it must be guarded by the will. We must stay the course to the end. We must break the toxic chains and entanglements of experience if we are to return to the mind and heart of our childhood .... which by the grace of God we faintly still remember. The destination is still known to all of us.

|

"Who then is greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven?" Then Jesus called a little child to Him,

set him in the midst of them, and said, "Assuredly, I say to you, unless you are converted [metanoia] and become as little children, you will by no means enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Therefore whoever humbles himself [throwing off the world's glory and the robes of office] as this little child [racing about, climbing trees] is the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven. Whoever receives one little child like this in My name receives Me [receives the living God!]." (Mt 18:1-5) |

This, of course, prompts another question: "What is the heart of Jesus?" St. John the Baptist knew. It is the heart of innocence: Behold: the Lamb of God, the Pure One. And His followers, now and today, must strive to have this same heart, to think these same thoughts, to cherish the same things, to be filled with a sense of wonder (as the Hermitage Sisters are). As a follower of this same Lord, St. Luke realizes this and wants to depict it for all prospective disciples to see.

St. Luke painted the first icon of the Mother of God. In this, he rendered an interior quality: of purity, simplicity, faithfulness, and holiness. But what would an icon of metanoia or sotería look like? It must depict a spiritual sensibility. He must find a way to describe deliverance from the toxic world and rescue from the poisonous atmosphere of adulthood.

Let us nominate a scene depicted in the public square: a man covered in the world's glory throwing off his dignity with abandon and reclaiming his boyhood name and, in the presence of all, exhibiting outlandish behavior. And yet when he climbs that towering Sycamore, safe from the world below, is not this man now half-way to Heaven? I am reminded of a Longfellow poem: "And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

Vivid!

Memorable!

Touching!

.... and apt to command the attention of everyone who sees it

—

an icon painted by the master,

the artist who founded the artform of verbal, holy icons.

How textured!

How nuanced!

How spiritually dimensional!

Truly, this art breaks through from our gritty world to

the good,

the true,

the beautiful,

as

otherworldly as the mysterious icon of the Mother of God.

Here is the Kingdom of Heaven.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.